[15]

A recursive tree

In the previous part we managed to draw a spiral recursively and make it stop when a condition was met. This taught us how to do the primitives if and stop.

In this post we will deal with the fourth example that was part of the scope of this project, a recursive tree:

to tree :length

if :length < 15 [stop]

fd :length

lt 45

tree :length/2

rt 90

tree :length/2

lt 45

bk :length

end

cs

bk 100

tree 160

The first thing we can see is that there is nothing there that we haven’t dealt with before in the past, except for the < in the if, because we have only implemented the logic for >. Let’s start with this.

We add a new delimiter “lesser than”:

delimiters: {

OPENING_BRACKET: "[",

CLOSING_BRACKET: "]",

PLUS: "+",

MINUS: "-",

MULTIPLIEDBY: "*",

DIVIDEDBY: "/",

GREATERTHAN: ">",

LESSERTHAN: "<"

},

Check that it is a delimiter:

isDelimiter(c) {

return c === logo.tokenizer.delimiters.OPENING_BRACKET ||

c === logo.tokenizer.delimiters.CLOSING_BRACKET ||

c === logo.tokenizer.delimiters.PLUS ||

c === logo.tokenizer.delimiters.MINUS ||

c === logo.tokenizer.delimiters.MULTIPLIEDBY ||

c === logo.tokenizer.delimiters.DIVIDEDBY ||

c === logo.tokenizer.delimiters.GREATERTHAN ||

c === logo.tokenizer.delimiters.LESSERTHAN;

}

And finally apply the logic in execute_if:

switch (operator) {

case logo.tokenizer.delimiters.LESSERTHAN:

condition = left < right;

break;

case logo.tokenizer.delimiters.GREATERTHAN:

condition = left > right;

break;

}

When we run the code we don’t see what we were expecting (a bit of a letdown, really):

It took me a while to get what was wrong when it was clearly in front of my nose, I even had to download the logs. This is an extract of the logs to show exactly what the parser did (because all the tokens were identified correctly, the problem was in the parser). When we check in the logs the turtle primitives that were executed we get:

Remember that in the code going backwards is calling going forward but with a negative value and turning left is just turning left with a negative value.

| Turtle in code | Equivalent |

|---|---|

| execute_forward(-100) | bk 100 |

| execute_forward(160) | fd 160 |

| execute_right(-45) | lt 45 |

| execute_forward(80) | fd 80 |

| execute_right(-45) | lt 45 |

| execute_forward(40) | fd 40 |

| execute_right(-45) | lt 45 |

| execute_forward(20) | fd 20 |

| execute_right(-45) | lt 45 |

So if we expand the LOGO script when the procedure is called, this is what happens:

cs

bk 100

tree 160

if 160 < 15 [stop]

fd 160

lt 45

tree 80

if 80 < 15 [stop]

fd 80

lt 45

tree 40

if 40 < 15 [stop]

fd 40

lt 45

tree 20

fd 20

lt 45

tree 10

if 10 < 15 [stop]

(the rest of the code is not run)

What is going on is that when we finish a call to a procedure we never return to the point where it was branched out to continue with the code, we just run a single branch. As we did with the loops having a loop stack (now called a code block stack) we would need a procedure call stack.

The procedure call stack

Now that we know we need a procedure call stack, and since we learned how to do the stacks with the loop stack it will be a lot easier. We just need to record when a procedure is called, run the procedure and when the procedure finishes go back to the point that we left it.

We start with create the variable in parse:

this.procedureCallStack = [];

The other two places are in jumpToProcedure to record it and in execute_end to return the control to the right token. When we take a look at jumpToProcedure we realize that we already have something we can use to store the information we need and that’s the variable procedureCallInformation:

this.procedureCallInformation = {

name: procedure.name,

parameters: values,

procedureCallLastTokenIndex: this.currentTokenIndex

};

This variable is used in 3 places:

jumpToProcedure(obviously, we found it there)execute_end(also obvious, to return the control to the right place)getExpression_Value: when we call a procedure with arguments and we want to know the value of the argument, for example here when we callfd :lenghtinside the procedureto tree :length, what is the value of:length.

Let’s show getExpression_Value:

getExpression_Value(result) {

console.log("my current token", this.currentToken);

switch (this.currentToken.tokenType) {

case logo.tokenizer.tokenTypes.NUMBER:

result.value = parseInt(this.currentToken.text);

break;

case logo.tokenizer.tokenTypes.VARIABLE:

let variableName = this.currentToken.text;

let parameter = this.procedureCallInformation.parameters

.find(p => p.parameterName === variableName);

result.value = parseInt(parameter.parameterValue);

break;

}

console.log(`getExpression_Value -> ${result.value}`);

}

The code for “variable” feels like it could be moved to another function so we can extract any call to the procedure to this new function and leave getExpression_Value free from it.

Let’s call it assignVariable:

assignVariable(variableName) {

let parameter = this.procedureCallInformation.parameters

.find(p => p.parameterName === variableName);

let value = parseInt(parameter.parameterValue);

return value;

}

And getExpression_Value, after removing a few console.log is:

getExpression_Value(result) {

switch (this.currentToken.tokenType) {

case logo.tokenizer.tokenTypes.NUMBER:

result.value = parseInt(this.currentToken.text);

break;

case logo.tokenizer.tokenTypes.VARIABLE:

result.value = this.assignVariable(this.currentToken.text);

break;

}

}

which looks cleaner. We haven’t done much so far, everything should work as before. The three places we need to look at are now:

jumpToProcedureexecute_endassignVariable

jumpToProcedure

The variable “procedureCallInformation” that was a property in the parser now we don’t need it so we create a local variable with “let”. We also add an extra logging.

let procedureCallInformation = {

name: procedure.name,

parameters: values,

procedureCallLastTokenIndex: this.currentTokenIndex

};

this.procedureCallStack.push(procedureCallInformation);

console.table(procedureCallInformation);

execute_end

Instead of

execute_end() {

console.log(`Starting: execute_end`);

let index = this.procedureCallInformation.procedureCallLastTokenIndex;

this.currentTokenIndex = index;

}

We will get the latest item from the stack.

execute_end() {

let item = this.procedureCallStack.pop();

this.currentTokenIndex = item.procedureCallLastTokenIndex;

}

assignVariable

Since before we had only one procedure, what we need to do is to check the last procedure in the stack without taking it out (that is done in execute_end). The easiest way to peek the value is to pop it, read what we need and push it back.

Therefore the code changes to:

assignVariable(variableName) {

let item = this.procedureCallStack.pop();

console.table(item.parameters);

let parameter = item.parameters.find(p => p.parameterName === variableName);

let value = parseInt(parameter.parameterValue);

this.procedureCallStack.push(item);

return value;

}

We run the code now, expecting to get a beautiful tree and… we get the same half rubbish tree we got before! why?

If we log every time we add something to the procedure call stack what are the values in the stack we can see that it contains 5 trees (the same as in our graph earlier when we did tree 160, tree 80, tree 40, tree 20, tree 10) but none of them are popped!! why?

The answer is just staring at us, and this is the sneaky part when dealing with recursive functions. The problem is with stop. What did we write in the little graph above where we show the 5 calls to tree? at the end it says:

“(the rest of the code is not run)”

and because it is not run, we never reach execute_end and therefore we never use the recursivity that we were trying to test in the first place. And why we don’t reach it? because when we do stop we do a complete stop for the parser. But inside a procedure stop really means: stop running this procedure and return control, which for us is the equivalent of “don’t run anything else in this procedure right now and move the index to point to the end of the procedure and this way we can call the code for execute_end.

So we create the function to skip until we reach the end of the procedure:

skipUntilEndOfProcedure() {

while (this.currentToken.primitive !== logo.tokenizer.primitives.END) {

this.getNextToken();

}

this.putBackToken();

}

We need to put back one token because in the loop we will move to the next one after end but we need to have end as the current token for our logic in execute_end work.

So in execute_stop:

execute_stop() {

this.skipUntilEndOfProcedure();

}

we don’t stop the parsing completely (only when pressing the UI button to stop).

Ready to try again? you will be pleased to know that it works as expected:

In the next part we will finally tackle how to use Spanish instead of English and you would be surprised at how easy it will be!

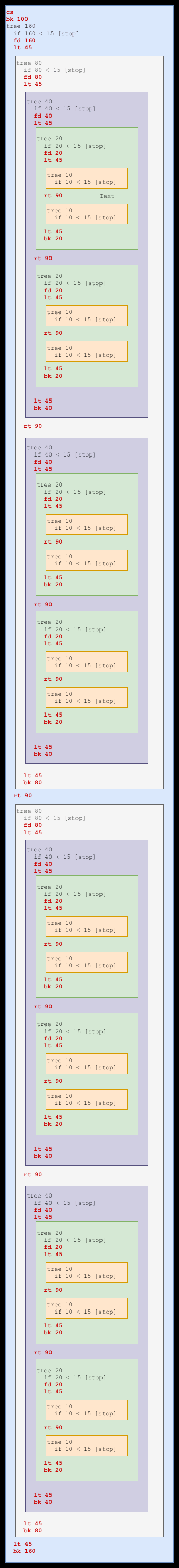

And just out of curiosity if you want to see how the tree code is generated, I made a graph with all the trees expanded one inside the other. If we follow all the turtle commands (in red) from top to bottom we will get exactly what this recursive tree example does.