[2]

Poor man’s tokenizer

In the previous part we established the file structure of the project, just a html file, one javascript and one css. We don’t use any external library or node.js, so everything will be done in the browser and in the console.

So… what’s a tokenizer? let’s start with what we want to achieve, one step at a time. We want to be able to run this script:

repeat 4 [fd 60 rt 90]

For the computer to understand it, it has to be divided in recognizable chunks (tokens)

So in this example, the tokens would be:

repeat 4 [ fd 60 rt 90 ]

and the program that translates the text into a sequence of tokens is (wait for it) the tokenizer (also known as lexer or scanner) but I prefer the term tokenizer because, well, it creates tokens. For more information, this article gives you a good introduction.

Since we are going to be working on this example for a while we may as well add it to the textarea element, and we remove the “Hello” text because we don’t need it anymore:

<body>

<textarea id="myTextarea">repeat 4 [ fd 60 rt 90 ]</textarea>

<script type="text/javascript" src="js/logo.js"></script>

</body>

You may have noticed that I left a space around the square brackets. This is done on purpose because the easiest way to separate the tokens is if they are individual words.

So some of you will start now with “let’s use regex” and yes, you can do something like this:

let tokens = textarea.value.match(/([^\s]+)/g);

console.log(tokens);

And we will get the desired result:

(8) ["repeat", "4", "[", "fd", "60", "rt", "90", "]"]

What this regex does is:

- Analyze the text inside the textarea (

textarea.value). This isrepeat 4 [ fd 60 rt 90 ] - Find all the matches (

gfor global, not only the first one) - The matches are for the regular expression between the two forward slashes, therefore

([^\s]+) - Whatever we try to match will be saved in an array, hence the brackets. So the expression is now

[^\s]+. - And that expression means: find any character that is not (

^) a space (\s) and it is followed by more characters that are not spaces (i.e. the delimiter is a space)

But since this is not going to be the final solution, do we need to use regex? My main issue is that when people use regex they tend to try more things with regex even if it is not necessary, and someone will try to solve a problem with a supercomplicated regex that it is difficult to read. Coming from C#, Jon Skeet has also the same thoughts.

We will do the simplest possible way for now:

let tokens = textarea.value.split(' ');

console.log(tokens);

And we will get the same result.

Tokenizer in a function

We will clean up the current javascript to remove the previous console.log test.

Also, since the textarea variable is going to be our future editor for the LOGO script we may as well start calling it editor. Our javascript code becomes:

function tokenizer(editorId) {

let editor = document.getElementById(editorId);

return editor.value.split(' ');

}

let tokens = tokenizer('myTextarea');

console.log(tokens);

and this looks much better since we encapsulate it in a function and we don’t hardcode the textarea element.

Tokens

So far we have an array of strings and we want to find out what kind of tokens they are. Let’s start looking at what kind of tokens we have in our example:

repeat 4 [ fd 60 rt 90 ]

Following Herbert Schild’s Small BASIC code in the book commented in here, these can be classified as:

| Token text | Token type |

|---|---|

| repeat | command |

| 4 | number |

| [ | delimiter |

| fd | command |

| 60 | number |

| rt | command |

| 90 | number |

| ] | delimiter |

and since the commands in LOGO are called primitives instead, we will use that word from now on.

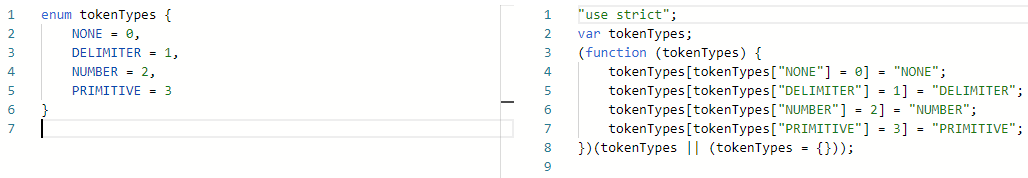

How do we encode the token types? if I were working in C# (or even typescript) we would use an enum. We don’t have enums in javascript (and I won’t enter the debate as to what is an enum or not) but we can take a look at how a typescript enum is transpiled to javascript using the typescript playground

Since we don’t know if we are going to keep the enum in the future, the easiest way to simulate an enum in javascript is with a json object:

const tokenTypes = {

NONE: 0,

DELIMITER: 1,

NUMBER: 2,

PRIMITIVE: 3

};

For my enums I always reserve the value 0 for the NONE value, i.e. a value that I can assign when I am not assigning anything yet. This will become more evident later.

So now, how do we use the token types? Since now we have classes in javascript, let’s create a Token class.

If we look at the table before we can see that two properties immediately stand out: text and token type. So our class looks like:

class Token {

constructor (text = "", tokenType = tokenTypes.NONE) {

this.text = text;

this.tokenType = tokenType;

}

}

Why do we give default values? personally, because it helps me with VS Code knowing that text is a string and that tokenType is a token type. Here we can see the reason why I have always a NONE value in my enums (or whatever we have in the json object).

Having the class, let’s start working with it. We need to modify the tokenizer function to try to identify the tokens. Before I jump to try making this into a class, let’s see how far I can go without adding any methods with prototype, which I am not fan of. We will use fat arrows instead.

To establish if a token is a delimiter, a number or a primitive we need to know what we consider a delimiter, a number or a primitive. Let’s start with the easy one, a number. We are going to allow integers only (we will see later why), so for us any string containing only [0-9] characters will be a number. This is a perfect case for using regex

Our function is now:

function tokenizer(editorId) {

let isNumber = (tokenText) => /^\d+$/.test(tokenText);

console.log(isNumber("ab12"));

console.log(isNumber("123"));

let editor = document.getElementById(editorId);

return editor.value.split(' ');

}

I’ve added a couple of tests to check if our regex is working as expected. The regex simply checks that the whole expression from beginning ^ to end $ is just number \d after number \d which is expressed as \d+.

In the console we will see that our console statements return false and true respectively.

For the delimiter, we need to have a list of delimiters. Since I have an enum of token types (please, humour me here with calling this json object an enum), it makes sense I have a list of delimiters; so far only [ and ]. Because I really need the text representation of the delimiter I won’t use any NONE value (also, I wouldn’t know what to use as the string representation of NONE).

const delimiters = {

OPENING_BRACKET: "[",

CLOSING_BRACKET: "]"

};

And the fat arrow function is straightforward, as we just compare two values:

let isDelimiter = (tokenText) => {

return tokenText === delimiters.OPENING_BRACKET ||

tokenText === delimiters.CLOSING_BRACKET;

};

Finally, the primitive. So far we have only three: repeat, fd and rt, so we will do the same as with the delimiters, another json object:

const primitives = {

FORWARD: "fd",

RIGHT: "rt",

REPEAT: "repeat"

}

And in the tokenizer:

let isPrimitive = (tokenText) => {

let lowercaseTokenText = tokenText.toLowerCase();

return lowercaseTokenText === primitives.FORWARD ||

lowercaseTokenText === primitives.RIGHT ||

lowercaseTokenText === primitives.REPEAT;

};

And our function so far (all together):

function tokenizer(editorId) {

let isNumber = (tokenText) => /^\d+$/.test(tokenText);

let isDelimiter = (tokenText) => {

return tokenText === delimiters.OPENING_BRACKET ||

tokenText === delimiters.CLOSING_BRACKET;

};

let isPrimitive = (tokenText) => {

let lowercaseTokenText = tokenText.toLowerCase();

return lowercaseTokenText === primitives.FORWARD ||

lowercaseTokenText === primitives.RIGHT ||

lowercaseTokenText === primitives.REPEAT;

};

let editor = document.getElementById(editorId);

return editor.value.split(' ');

}

As someone can write REPEAT or repeat (or if you are feeling adventurous a mix like RePeAt) we match against the lowercase value.

So we just need to check the tokens after splitting the text from the editor with spaces and start creating Token objects.

In the tokenizer after IsNumber(), IsDelimiter() and IsPrimitive():

let editor = document.getElementById(editorId);

let tokenTexts = editor.value.split(' ');

let tokens = [];

tokenTexts.forEach(tokenText => {

if (isNumber(tokenText)) {

tokens.push(new Token(tokenText, tokenTypes.NUMBER));

} else if (isDelimiter(tokenText)) {

tokens.push(new Token(tokenText, tokenTypes.DELIMITER));

} else if (isPrimitive(tokenText)) {

tokens.push(new Token(tokenText, tokenTypes.PRIMITIVE));

}

});

return tokens;

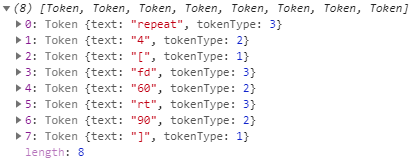

And that will return a nice array of tokens:

ToString() or not ToString()

I am not overly happy that the console shows me the properties of the json as integers, but after all it is my fault because that’s the value of the property in json.

Would it be possible to make the string representation of the Token nicer to the eye, like in C# when we do

public override string ToString()

{

return "something";

}

Yes, we can do that in javascript with get[Symbol.toStringTag]()

So if we add in the Token class:

get[Symbol.toStringTag]() {

return `"${this.text}" - ${this.tokenType}`;

}

when we run our code, we get exactly the same as before, what happened?

What we are checking in the console is an array of tokens, not an array of the string representation of a token.

So if we change console.log(tokens) to console.log(tokens.toString()) we get:

[object "repeat" - 3],[object "4" - 2],[object "[" - 1],[object "fd" - 3],[object "60" - 2],[object "rt" - 3],[object "90" - 2],[object "]" - 1]

We can’t remove the object at the beginning, so this is as good as it gets. But wait a minute, we still have numbers instead of the enum values, and everything appears in one line. Let’s focus on the latter.

In the console we are not getting the text representation of tokens, we are getting the text representation of an array of tokens, which is different. If we wanted to see the tokens each in one line, instead of console.log(tokens.toString()) we can do

tokens.forEach(token => console.log(token.toString()));

And for the string value of the token types? let’s think for a moment. We have a json object with some keys (primitives) and values (numbers), so the code to get a key for a specific value is:

let tokenTypeKey = Object.keys(tokenTypes)

.find(key => tokenTypes[key] === this.tokenType);

where first we get a list of all the keys with Object.keys(tokenTypes) and we find the one that satisfies the right numeric value. With this in the console we would get:

[object "repeat" - PRIMITIVE]

[object "4" - NUMBER]

[object "[" - DELIMITER]

[object "fd" - PRIMITIVE]

[object "60" - NUMBER]

[object "rt" - PRIMITIVE]

[object "90" - NUMBER]

[object "]" - DELIMITER]

which is exactly what we wanted to have, congratulations. Note that I could have added the code to get the keys somewhere else but since I just want to show the string representation when we convert the Token to string, nowhere else, I decided to use the code only in Token.

In the next part we are going to use this tokenizer inside a parser and we will be able to run this code (in the console) before we start showing the turtle!